I have been reading this paper and want to share some interesting ideas that are presented. If you haven’t already, take a look at part 1.

Note: This is not my work, I just use the word “our” to make it easier for me to communicate some ideas.

A Naive Approach

The first thing to notice is that among the set of intermediate values computed at a node, each of the other nodes require some subset of them. So here’s an idea: multicast all the intermediate values available to the node. When another node receives all of these intermediate values, it keeps what it requires and discards the rest. Thus each node has to only make a single multicast. Have we reduced the communication load? Notice that while we reduced the number of messages that are exchanged, the size of this single message is infact the sum of the individual sizes of each message exchanged in the previous scheme. Thus there is no overall improvement.

A Coded Approach

Now it seems we have run into a wall. How do we communicate these intermediate values with multicasts without blowing up the message size? Enter Coding Theory magic! Here we’ll try to construct a scheme that acheives this. We’ll explore this using the example in the previous post. Lets try to construct this for \(r=2\).

Distributing the files

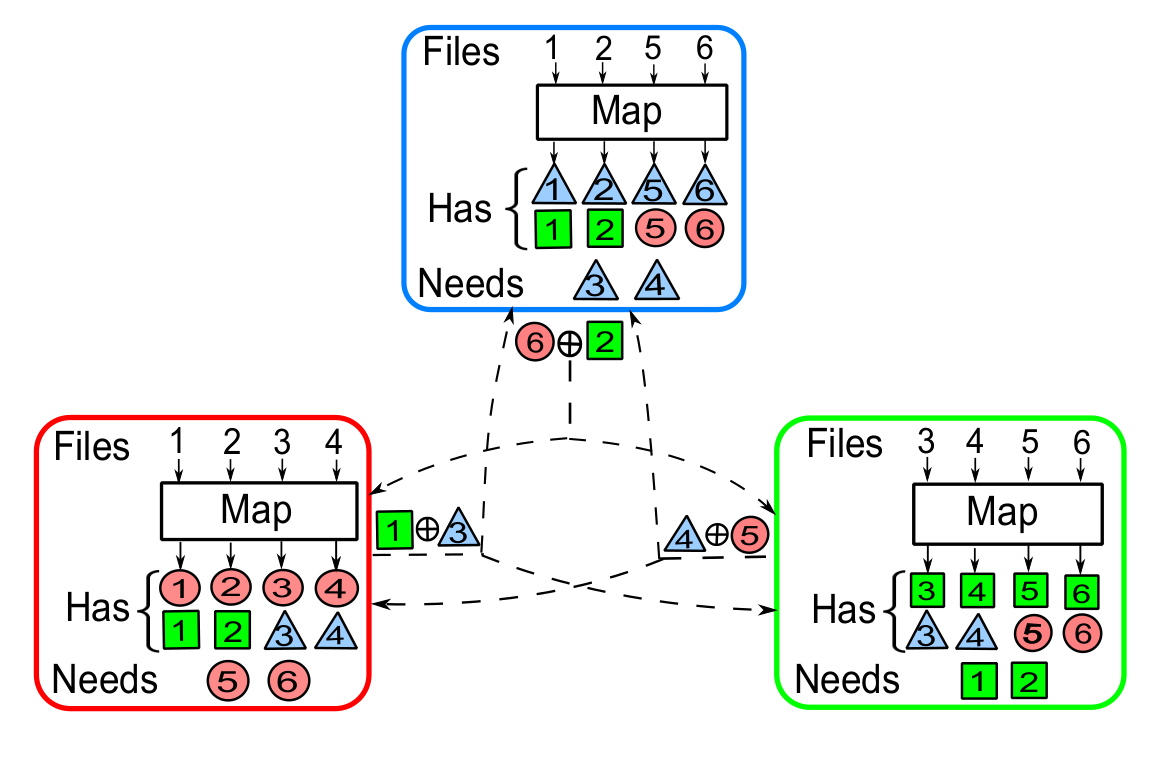

Recall we have 6 files. We have to distribute these files so that \(r=2\). A good idea is to start with a distribution where each file is available to the same number of nodes. One idea is to give each file to two nodes. There are \({6 \choose 2} = 3\) such pairs of nodes, thus each node gets \(\frac{6}{3} = 2\) files. For example lets assign node 1 and 2 files 3 and 4, nodes 1 and 3 files 1 and 2 and nodes 2 and 3 files 5 and 6 (see the diagram). Why this is a good idea will soon be apparent.

The Magic: XOR

Now node 1 has computed the intermediate values \(v_{1,1}, v_{1,2}, v_{1,3}, v_{1,4}\) for its function \(q_1\). We can also make it compute function \(q_2\) on the files required by node 2 (files 1,2) and \(q_3\) on the files required by node 3(files 3,4). These correspond to intermediate values \(v_{2,1}, v_{2,2}\) and \(v_{3,3}, v_{3,4}\) respectively. Each node does the same. The state is as seen in the diagram where the color \(c\) and number \(i\) corresponds to intermediate value \(v_{c,k}\).

Now consider node 2. Let us assign the responsibility of delivering it \(v_{2,1}\) to node 1 and \(v_{2,2}\) to node 2. We do this similarly for other nodes. Here is where the magic happens. Instead of unicasting each intermediate value the node is responsible for, the node multicasts the XOR of all these values. As you can see in the diagram, node 1 multicasts \(v_{2,1} \oplus v_{3,3}\), node 2 multicasts \(v_{1,6} \oplus v_{2,2}\) and node 3 \(v_{3,4} \oplus v_{1,5}\).

This is where we take advantage of how the files were distributed. Notice that both node 1 and 2 can supply \(v_{3,3}\) to node 3. Thus when it receives \(v_{2,1} \oplus v_{3,3}\) that was multicast by node 1, it can easily recover \(v_{2,1}\) by simply XORing with \(v_{3,3}\). Thus each node needs to only make a single multicast during the data shuffling phase.

Recall the communication load is the total amount of information exchanged normalized by the total size of all the intermediate values. Here there were 3 messages (say each of size \(T\) bits) and a total of \(3 \times 6 \times T = 18T\) bits of intermediate values. Thus we get a load of \(\frac{1}{6}\). Recall that for the uncoded scheme, the communication load was given by \(L(r) = 1 - \frac{r}{K}\). For \(r = 2,\; K=3\) this gives \(\frac{1}{3}\). Thus the coded scheme cuts the communication load down by half!.