I have been reading this paper and want to share some interesting ideas that are presented.

Note: This is not my work, I just use the word “our” to make it easier for me to communicate some ideas.

The Map Reduce framework

Here I’ll touch upon the idea behind map reduce, if you have an idea of how it works, skip to the next section. Consider a motivating problem.

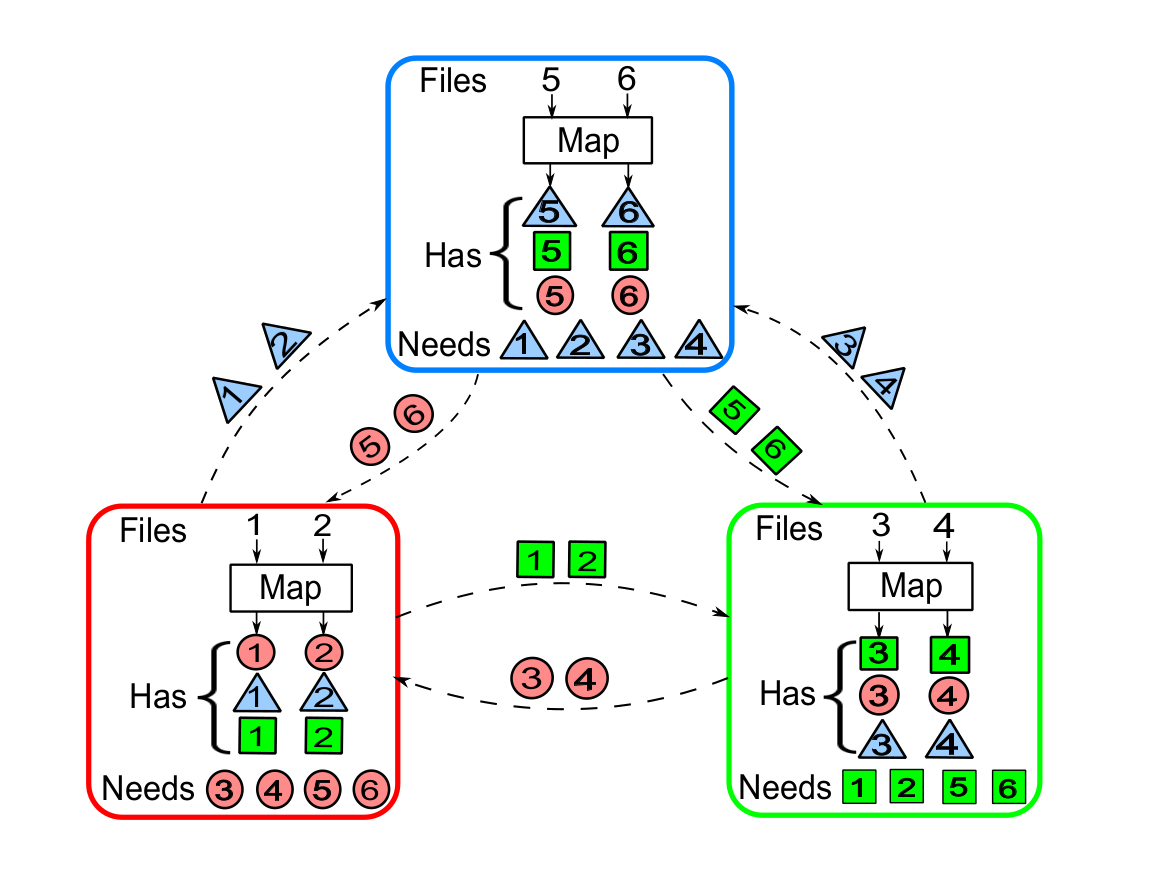

We have a set of 6 documents and 3 words. We are interested in counting the frequency of each of these words in the documents.

In a single-node setting, we would iterate over the words in each document and check whether they belong to the set of words we’re interested in. Let us consider a distributed setting where we have 3 nodes each having 2 of the documents. We can use the same naive algorithm here as well: each node sends the documents it has to node 1 and node 1 runs the algorithm. However, we can do better.

Let us assign the responsibility of computing the frequency of the first word to the first node. That is, at the end of this process node 1 contains the frequency of word 1 across all documents. Similarly for node 2, word 2 and node 3, word 3. Consider a function called \(map()\). The function \(map()\) takes a document as input and outputs 3 values: the frequencies of the three words in the document. Now if each of the nodes performs the map function on the two documents it posseses, each node will have a total of 6 values. This is known as the map phase.

Now, for node 1 to compute the frequency of word 1 across all documents, it requires the frequency of word 1 in the 4 documents that it doesn’t possess. These values have already been computed by the other nodes during the map phase. Thus each node sends out 4 values to the nodes that require them. This is known as the data shuffling phase.

Finally, when the nodes receive the required values, they need to combine them with the values that are already computed. This function is called the \(reduce()\). In this case, reduce can be done by a simple addition. This is known as the reduce phase.

More generally, consider \(N\) input files \(w_1, w_2, \cdots, w_N\) distributed across \(K\) nodes. Consider \(Q\) output functions \(q_1, q_2, \cdots q_Q\) where each can be decomposed as \(q_i(w_1, w_2, \cdots, w_N) = red_i(m_{i,1}(w_1), m_{i,2}(w_2), \cdots, m_{i,N}(w_N))\). Here \(m_{i,j}(w_j) = v_{i,j}\) is called an intermediate value.

In the simple example above, the output function \(q_i\) outputs the frequency of word \(i\) across all documents. Each map function \(m_{i,j}\) outputs the frequency of word \(i\) in document \(j\). The reduce function \(red_i\) simply sums over each \(v_{i,j}\).

Computation Communication Tradeoff

In the example we explored in the previous section, each file was mapped to exactly one node. Each function was also mapped only to a single node. As a result, there was quite a bit of communication required to shuffle around the intermediate values. Now in message passing systems like MPI, a multi-cast to a collection of nodes has the same communication overhead as a unicast to a particular node. Thus an interesting question that we can ask is: if we computed more intermediate values during the map phase, can we harness multi-casts to reduce the overall communication overhead. To actually reason about this, we must first have a formal notion of computation and communication.

Consider a single output function. We define computation load \(r\) as the total number of map functions computed across all nodes normalized by \(N\). For example, if \(r=1\), each map function is computed only once.

We define the communication load \(L\), as the total number of bits exchanged during the shuffling phase normalized by the size of the \(QN\) intermediate values.

Thus the Computation Communication Tradeoff question is given a value of \(r\), what is the smallest value of \(L\) that can be acheived.

The Tradeoff for Map Reduce

In Map Reduce, as described previously, \(QN\) intermediate values are required across the \(K\) nodes. Assume node \(i\) maps some subset of the files \(M_i\). Also assume that functions are symmetrically allocated: each node computes \(\frac{Q}{K}\) functions. Thus for node \(i\), \(M_i \frac{Q}{K}\) intermediate values are already available. Summing over all possible nodes, we get \(\sum_i M_i.\frac{Q}{K} = rN . \frac{Q}{K} = \frac{rQN}{K}\). Therefore \(L(r) = 1 - \frac{r}{K}\).

Can we do better?

Notice that as we increase the value of \(r\), the communication load only decreases additively. This begs the question, can we do better? Wouldn’t it be great if we could reduce this load multiplicatively? It turns out, we can! In the paper, the authors propose a Coded Distributed Computing scheme that acheives \(L(r) = \frac{1}{r}(1 - \frac{r}{K})\). Not only this, they also go on to prove that this is in fact an information theoretic lower bound.